Today is the official 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 landing on the Moon (July 20th, 2019). As a change of pace from the usual tributes and histories concerning the anniversary, I am posting a reworking of an excerpt of an article I wrote for the Asterism (AAI’s newsletter) some years ago where I compare the Apollo missions to their fictional ancestor, which was written by Jules Verne. Enjoy.

Probably one of the first authors who wrote what we could call science fiction was Jules Verne. And he also had quite a knack for predicting things in the future. Many (evidently including the U.S. Navy) believed that “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” foretold the nuclear submarine since the Nautilus was said to require a special substance mined on an island in order to run. And his most predictive story “Paris in the 20th Century” (which predicted the fax machine, among other things) was rejected by Verne’s publisher as being too far-fetched, even by Verne’s standard. But the story that will be discussed here is “From the Earth to the Moon” published in 1865.

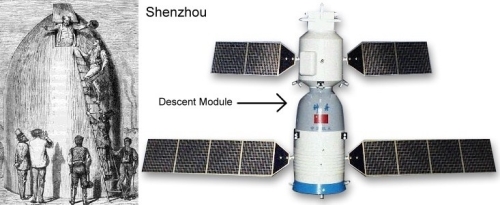

The vehicle used by the space travelers was the Columbiad. It was a capsule made mostly out of aluminum, an exotic wonder material of that era, like carbon nanotube composite is in our time. But Verne made the right choice since aluminum is a major component of modern spacecraft for the same reasons Verne chose it – it is an extremely light metal. However, Verne either ignored or was unaware of atmospheric friction and there was no mention of any sort of thermal protection system on the Columbiad. Even though Jules Verne never thought of rockets having sufficient power to launch a space vehicle (this was about 25 years before Konstantin Tsiolkovsky would first describe space rockets), he did mention that the Columbiad was equipped with maneuvering thrusters for use in space, like modern spacecraft. Then there is the shape of the Columbiad itself. It is always depicted as having a blunt shape like an artillery shell, not the gumdrop shape that the Apollo capsules, NASA’s Orion capsule, as well as Boeing’s CST-100 have, but it is very similar in shape to the descent modules of the Russian Soyuz and Chinese Shenzhou capsules, as illustrated by a comparison between Columbiad and Shenzhou below (not to scale).

A comparison of the Columbiad (on left) and the descent module of the Chinese Shenzou spacecraft (on right)

While the method Verne’s astronauts used to leave the Earth, having their capsule shot out of an enormous cannon, was way off target, many other aspects in the story were extremely predictive. For instance, the launch site is located in Florida, not too far from the present-day Kennedy Space Center. While this might seem to be a lucky guess, it wasn’t. Verne wrote that the organizers of the mission had a debate over the launch site between Florida and Texas, much like Congress had in the early days of spaceflight. Florida wound up being chosen for the same reason it was in reality – latitude. When a rocket is launched, it is generally sent on an easterly path. The reason for this is to take advantage of the Earth’s rotation to gain a little extra velocity. And since the Earth rotates as a solid body, this velocity gain is larger the closer you get to the equator (the European Space Agency has their launch site in South America). Verne’s astronauts were Americans and Verne knew that Florida was as far south as the United States went in those days.

In space, the astronauts on board the Columbiad pass the time by performing some scientific experiments – an activity that their real-life modern counterparts also do. But the resemblance to a modern flight doesn’t stop there. The Columbiad flight plan called for it to fly around the Moon and then head back to Earth. In NASA jargon, this is called a free-return trajectory and those who remember Apollo 13 (the actual mission or the Ron Howard film) know that this was the trajectory the crew had to get their crippled spacecraft back on to return home. And, foreshadowing what would become standard procedure in the Apollo missions, the Columbiad crew made observations of the Moon as they flew around it, though their attempt to study the unlit portion of the far side of the Moon was less than successful.

Finally, Verne ends the mission by having the Columbiad splash down in the Pacific near Hawaii, where it and the crew are recovered by a specifically designated vessel. Again this is quite similar to how the actual Apollo missions went. About the only major difference was that the real life U.S. Navy recovery teams found the Apollo capsules much quicker than Verne’s recovery team found the Columbiad.